Apart from the selection and fortunes of the West Indies Cricket team, there is no other issue that evokes, in this region, a richer, more sustained, more fierce, and more misplaced commentary than the purposes and workings of the Caribbean Single Market and Economy.

In both instances, the debate seems to be inspired by the desire of the people of the Caribbean for the region and its institutions to succeed, and the unwillingness therefore to accept any departure from full effort and best practice.

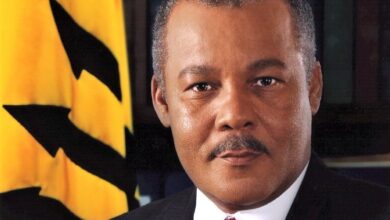

My mission in Kingston this evening is to share with you a perspective, from the vantage point of the Prime Minister with the lead responsibility for the CSME, on the critical issues pertaining to its establishment and on the way forward.

I sense, as do all the rest of us who are concerned with this most vital regional enterprise, the need for a sustained and successful engagement with the people of the region on matters such as what exactly are we seeking to do, why we are seeking to do it, what has been accomplished to date, what remains to be done, what is expected of each of us, whether it can be done, and if it is done, what will be the probable outcome.

THE CSME – WHY AND WHAT

The creation of a Caribbean Single Market and Economy – as the concept literally implies – is an effort to cause the participating Caribbean nations which have hitherto functioned as 14 separate and distinct markets and economies, each governed by their own rules and divided from each other by formidable barriers, to be organized and to be made to operate in the future effectively as one market and one economy, free of restrictive barriers, and governed by common rules, policies and institutions.

As conceived, it will be the most ambitious enterprise of any kind ever to be carried out in the Caribbean.

As a form of economic integration, it is exceeded, among regional economic groupings, only by the European Union in respect of the depth and scope of its provisions, and in the degree of structural change it is intended to achieve in respect of the participating national economies.

To fully appreciate the scope and complexities of its provisions and the significance of the purposes it is intended to achieve, a bit of comparative history would help.

The CSME is intended to enable us to correct deficiencies in the systems and policies we have relied upon to manage our respective economies for an extended period, to replace earlier and more modest forms of economic integration which were far too limited in scope to be effective, and to serve as the platform from which, and the institutional mechanism by which, we integrate the region into the evolving global economy.

It is beyond dispute that the tradition and the tools of economic management associated with the separate, inward looking, insular economic development model which has typified the Caribbean throughout most of its history have retarded the economic progress of the region in many fundamental ways. The formidable array of restrictions on cross-border economic and financial transactions, the official constraints on the use and mobility of factors of production, and the great mismatch of basic macro-economic policies as practiced by the respective Caribbean States have overtime reinforced the tendency to underdevelopment in the region. They have done so by prohibiting the rational and optimal use of resources, preventing the emergence of enterprises that are capable of achieving appropriate scale and competitiveness, and have accentuated a “dog-eat-dog” approach to the management of our economic affairs that has been hardly conducive to sustained growth.

The initial regional response to correct this took the form of the creation of CARIFTA in 1968, which as a simple free trade area, merely removed tariffs on the intra-regional trade in goods produced within the region.

However, the mere removal of restrictions on intra-regional trade in goods will hardly ever be a major stimulus to regional development since the scope for “tariff-reduction-induced” growth, limited to regional transactions, is small and the driving force for development is not regional but international demand.

Hence in 1973, through the Treaty of Chaguaramas, which created CARICOM, the region sought to move to a higher plane of economic integration in the form of a limited common market. This new integration arrangement retained provision for the liberalization of the trade in goods, added a common external tariff, made token and very limited provision for the removal of restrictions of the movement within the region of capital and services, and some modest provision for the coordination of economic policies. No provision was however made for the free movement of people and skills.

A limited form of integration will always give rise to limited benefits. And so it was with the limited Common Market that was initially enshrined in the Treaty of Chaguaramas. Since 1973 there has been modest growth in intra-regional trade in goods, largely to the benefit of the country (Trinidad & Tobago) that has the attributes to be the most competitive in the sphere. There has, however, not been a great surge in intra-regional service trade, nor robust cross-border capital flows, nor the creation, except in a few rare instances, of Pan Caribbean companies, drawing upon the resources wherever available in the region, to forge enterprises of a scale to compete successfully within and outside the region.

The limited common market as conceived in 1973, caused no great transformation in the Caribbean economy in the subsequent 15 years. Yet, a great transformation was warranted. For in addition to its long-standing difficulties in maintaining stable growth, the region, and its affairs were increasingly being drawn into an international scheme of things where the very barriers on economic transactions which the region had imposed on itself were being dismantled, or proposed to be dismantled, in relations between nations across the globe.

The decision in 1989, to replace the limited Common Market, as enshrined in the Treaty of Chaguaramas, with a Single Market and Single Economy was fully warranted by the frustrations of a difficult economic past, and the prospect of an even more challenging economic future.

The concept of a Caribbean Single Market and Economy as espoused and accepted in 1989 envisioned that the region should be reconstituted to become a single market space in which not just goods, but also services, people, capital and technology should freely circulate, and rights of establishment of enterprise anywhere in the region should be enjoyed by the removal of the fiscal, legal, physical, technical and administrative barriers which have historically prevented such activities from taking place.

The concept also embodied the notion of a single Caribbean economy, based upon the pursuit of, as far as practicable, unified and harmonized economic and monetary policies. Specially, it called for the pursuit of a common trade policy, provision for the coordination of efforts to develop all of the productive sectors, a common competition policy, a common approach to consumer protection, dumping, subsidies and business development, a regional transportation policy, fiscal harmonization, a harmonized approach to capital market development, macro economic policy convergence, special measures to treat to the needs of disadvantaged sectors, regions, and countries, and the creation of new institutional arrangements to support and regulate cross-border economic liberalization and to resolve and to settle disputes.

WHAT HAS BEEN DONE

At Grand Anse in 1989, the Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community decided that such a new CSME, embodying the market liberalization and economic harmonization and unification features as just described, should be created at the earliest opportunity and by 1993.

The commitment to such a date reflected more a heroic sense of urgency rather than a pragmatic appreciation of the complexity of the task, and the variety of measures at the technical, legal, institutional, financial and constitutional nature that are required to transform 14 economies, that had evolved as separate entities, into a single economy.

Indeed, the only comparative experience, that of the European Union should have been a brake on Prime Ministerial enthusiasm in 1989.

For Mario Monti in “Europe – The Single Market and Tomorrow’s Europe” had this to say:-

By the mid 1980’s, it began to dawn on many that after nearly 30 years, the European Community still had no real common market, and that many of the freedoms prescribed in the Treaty of Rome (1957) for capital, goods, services, and people remain a dead letter”.

The European Single Market was only created in 1992 having been conceived in 1957, and as a construct and concept, it is still evolving.

By comparison the process to create a Caribbean Single Market and Economy has been rapid fire.

The technical work to define what would be involved in such an exercise, and how the CSME should be structured was undertaken by 1992.

It was next decided that in so far as the original Treaty of Chaguaramas did not make provision for a CSME, the Treaty would have to be amended by the articulation of a number of protocols to change the organs of CARICOM, to remove restrictions on capital movement and the provision of services, rights of establishment of enterprises, movement of people and skills, protocols on regional agricultural, industrial, and other sector policies, transport, trade, competition, special measures for the disadvantage and new mechanisms and institutions for dispute resolution including a Caribbean Court of Justice.

That essential legal work, under the auspices of an Inter Governmental Task Force involving region-wide consultations and negotiations, and the forging of a consensus on that wide range of complex issues, all requiring decision making in 14 separate capitals, was undertaken and the Treaty of Chaguaramas was revised and signed in 2002 to legally establish the CSME.

The Caribbean Single Market and Single Economy having been given a legal personality, the next step has been to bring it into operation .

Given the scale and complexity of what has been conceived, a work programme for the implementation of the provisions of the CSME has been devised, based upon very clearly defined priorities.

In this respect the chief priority has been attached to the implementation of the provisions to remove restrictions on the movement of people, capital, the provision of services, and the rights of establishment of enterprise.

Member countries have agreed to cease introducing new restrictions in these spheres, to notify Caricom of all existing restrictions, and to pursue a phased agreed programme to remove the restrictions by 2005.

Three countries (Jamaica, Barbados, and Trinidad & Tobago) have agreed to accelerate their implementation schedules and honour their obligations on this matter by 2004.

At the start of the exercise, it was determined that over 350 restrictions, mostly affecting rights of establishment, the movement of natural persons and cross-border trade in services, requiring amendment to some 400 legal and administrative instruments, would be affected by the programme.

It has very clearly therefore to be understood that we have come to a place and time when the creation of a Caribbean Single Market and Economy does not just involve simple administrative actions such as the removal of tariff barriers at ports of entry. It now involves the conferment of rights, freedoms and obligations by states, to be enjoyed by citizens and enterprises, that are to be explicitly expressed in provisions set out in domestic law, based on a body of community law which is now being drafted.

The domestic legislation principally to be affected includes customs, company, intellectual property, registration of professions, exchange controls, alien landowning and various existing national laws containing fiscal measures which have been held to be discriminatory in their treatment of local and regional enterprises and activities.

It will be a tall order and a busy year for the Parliaments of Jamaica and Barbados to discharge our obligations. But it can and must be done.

In such a context, the second and related priority has been to create a Caribbean Court of Justice invested with an original and mandatory jurisdiction to apply and interpret the legal provisions pertaining to the CSME. Without such a Court, to give certainty and predictability to the application of the legal provisions set out in the revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, consumers, businessmen, investors and participating states will not be able to repose full confidence that the arrangements for the CSME will be applied fairly and consistently in every place, time and circumstance in the region. Indeed, Barbados would have a difficulty participating in the CSME without the greater legal certainty and enforceability of its provisions that the CCJ now makes possible .

The arrangements to ensure the judicial and financial independence of the Court and to ratify its instruments, thus enabling it to be brought into existence, have been completed. By this action, the new CSME has been given a fair chance to be created and to succeed.

WHAT ALSO NEEDS TO BE DONE

A lot more however remains to be done to bring the Caribbean Single Market and Economy fully into existence.

First, Chapter Four of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas sets out an ambitious Agenda for cooperation in the articulation and implementation of policies and programmes for sectoral development. It prescribes a regional programme of cooperation for all of the main sectors, setting as its goal their market-led, internationally competitive and sustainable production of goods and services. It contains a regional charter for micro and small Economic Enterprise Development, a common agricultural policy, a framework for regional human resource development, a regional technological development programme, a community investment policy, a policy for environmental and Intellectual Property Protection, for the development of the social infrastructure, the harmonisation of Investment Incentives, macro economic policies, industrial relations and comprehensive development of the financial system.

The satisfactory implementation of such arrangements for economic and financial harmonization and cooperation, as specified in Chapter Four, would give a tremendous boost to the growth prospects of all Caribbean economies, be a spur to the creation of competitive enterprises and would open up new opportunities for investment and for the rationalization of the use of existing productive capacities on a scale never before contemplated in the region.

In compliance with its terms, already, a common regional fisheries regime has been tabled for consideration. Within the context of its provisions, there is the possibility for the pursuit of a common approach to the rationalization of traditional export production, in the face of the loss of preferences. Equally, we are at a place and time when the implementation of a regional energy supply and pricing policy and programme, based on respect for the National Treatment and Most Favoured Nation Treatment precepts as enshrined in Articles seven and eight of the Treaty must be carried through.

Concerted action in the joint development of our Tourism and Financial Services sectors is also provided for. It is imperative for example that within the context of Chapter Four obligations our region, in which 50% of the international cruise business originates, creates its own regional cruise line to deepen the value added that accrues to us individually and collectively from the only industry in which the Caribbean enjoys a dominant market position globally.

The implementation of the provisions set out in Chapter Four of the Revised Treaty concerning sectoral development also lends itself to the fostering of an entirely new partnership relationship among the regional private sector, the labour movement, the institutions of the civil society, our University and tertiary training institutions and respective regional governments.

The definition of the manner in which such a partnership should be structured and should take effect is urgent and must engage us immediately in order for us to move forward the process of embedding the workings of the CSME in the sectors’ performance and in the functioning of the economy at the level of the enterprise.

At the end of the day, the CSME is intended to give rise to more competitive economies. As we seek to implement it, we must be guided by the precept that Governments do not compete – enterprises do. We must use the CSME therefore to evolve more competitive companies. The measures for sectoral development and the related framework for the operation of enterprises within the common regional economic space will facilitate this and must be brought into full functioning as soon as possible.

To bring the CSME fully into operation, important future work must also be undertaken at the domestic and regional level to implement the measures relating to competition policy and the regional policy pertaining to subsidies and dumping. Trade and economic activities in the regions must not only be free but must also be fair.

Of equal significance is the task before us to complete the programme for the establishment of regional institutions and institutional arrangements that would allow the single, unified economic space to be occupied on fair and equal terms by all. Important in this respect will be the creation of a Regional Competition Commission, the Caribbean Regional Organisation for Standards and Quality, the Regional Accreditation Unit, the Regional Development Fund, and the list of Regional Conciliators and Arbitrators to settle disputes that need not go to the Court of Justice.

We are all in this, equally and together.

It will also be difficult to fully convert the individual Caribbean economies into a single Caribbean Market and Economy in the absence of a common currency or at a minimum, an agreed workable mechanism for the convertibility of existing currencies in a manner that minimizes the costs and exchange risk forced by entities involved in cross-border transactions.

The matter of a common currency has been taken off the agenda because the macro-economic conditions necessary to create the conditions of stability to support a common currency do not now exist. This however merely accentuates the need for concerted macro-economic reform and the successful carrying out of a policy convergence programme as essential aspects of the creation of a Single Market and Economy.

Above all else, the creation of a CSME challenges the Caribbean to revisit and to revise its instruments for regional governance.

In 1973, Caricom was created to be a Community of Sovereign states. In this political capacity it was created to carry out a limited form of economic integration, most of which involved only administrative action at ports of entry.

It therefore contemplated no transfer of national sovereignty nor the devolution of authority, in relation to decision making, to regional institutions.

The creation of a CSME is an entirely different matter. It will require far reaching legislative and institutional initiatives, whose incidence must be given certainty for stakeholders to have confidence in the process.

In Europe, which is the only other region that has sought to institute a process of integration similar to that of Caricom, regional decisions became European Directives enjoying the force of Community Law and obliged to be embeded in the national law. The European Council, the European Commission and the European Parliament have all been empowered to participate in decision making, ensuring that the process of implementation becomes certain and effective.

Under our present system for Regional governance, the Caribbean will attempt to establish a single economy relying almost entirely on inter-governmental cooperation and harmonization exercises that avoid the infringement of national sovereignty.

The full implementation of the provisions for the CSME will, in such a context therefore, be left to the discretion of the least ready and obliging member.

The arrangements for the implementation of the CSME now allow member states to provisionally apply the measures contained in the revised Treaty of Chaguaramas.

Too much is at stake however for us not to revisit issues of governance and to bring greater certainty and transparency to the process, as we hope to do next week at Ocho Rios when issues of regional governance will be considered by Heads.

I close by sharing a perspective, not of the Prime Minister with lead responsibility for the CSME, but as a Prime Minister of a participating state.

The CSME is the first realistic initiative that allows Barbados the prospect of escaping from the constraints imposed on us by small land, market and population size and limited natural resources.

It is not easy fully developing a country that is only 166 square miles in area with a population of 260,000 souls.

Better the larger market, and the wider set of options that come from being able to cooperate in the joint use of our collective resources with our neighbours.

We envision that the CSME will stimulate the creation and functioning of stronger Barbadian enterprises. We anticipate that participation in it will allow us to carry out far reaching economic reforms, testing them first in the regional environment before exposing ourselves to the risk of applying such policies in new extra regional relationships.

We recognize that we will have to make tough decisions.

We recognize that there will be areas of commodity production where we will not be competitive and where we will have to yield to regional competitors. We anticipate however that the liberalization of services especially offers us an opportunity for expanded production that can compensate for any loss in commodity production.

We are therefore resolved to go as fast as possible and as far as possible in honouring our commitments. We have thus already changed our Constitution to facilitate the operating of a Caribbean Court of Justice. We have also enshrined the revised Treaty of Chaguaramas into our domestic law.

Our Parliament will over the next twelve months be fully engaged in enacting the provisions to allows us to honour our obligations as specified in the revised Treaty.

It is an exercise that comes with some enormous political risk. But it will be in the service of a great regional and national cause.

As Norman Manley asserted here in Jamaica in 1947 “Great causes are not won by doubtful men”.

Now is not the time to doubt ourselves.

And I thank you for the opportunity to make that statement here in Jamaica where so much effort for the transformation of our region has originated.